History of the

Minnesota Chippewa Tribe

Introduction

An important aspect of any Constitution is to outline the rule of law for the nation and creating a system of governmental powers that outlines the rights of members and responsibilities of elected officials. The articles are like chapter headings, describing the purpose of each portion, each article is then separated into sections, like paragraphs. One Article grants each RBC the authority to make decisions on their own reservation.

Many constitutions have a three branch government that check and balance each other, typically a legislative branch that makes laws, an executive branch that executes the laws, and a judicial branch that interprets the laws. Our MCT Constitution does not have a three branch system (see Native Nation Building videos for more information) instead our elected officials serve as lawmakers, executors, and ultimate decision makers; in fact in 1980 the TEC issued an official interpretation that they (the TEC) were the only ones who could interpret the MCT Constitution. There was no mention of a court or judiciary system when the MCT constitution was developed. Constitutions also outline who their citizens are and the boundaries of their jurisdiction. Over time our MCT Constitution has changed.

After the passage of the the 1934 Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) each nation/band/reservation had to vote to accept or reject the IRA.

Election Results: Accept or Reject the IRA:

While Fond du Lac was ten votes shy of meeting the 30% threshold required by law to make the IRA election valid, oddly the solicitor held that since a majority of votes cast were in favor, "They have not voted to exclude themselves."

The Bureau of Indian Affairs expected that each reservation/band would organize an independent government. In fact, in 1933 Commissioner Collier wrote: "Since the Chippewas of Minnesota do not reside on the same reservation but on several reservations, it is our opinion that the several bands will have to organize individually." But a local BIA employee, Jacob J. Munnell (Leech Lake), argued that the Minnesota Chippewas were "one tribe with several reservations." He further asserted, "We are not residents of any one reservation. That we have no organized band, and that under this reorganization act we cannot incorporate separately we decided that the Chippewas of Minnesota should be incorporated under one organization and we trust that you will approve of the action taken." Organizing six bands/reservations into one government would save the Indian Office a significant amount of work. In addition, the argument to organize one government was probably connected to the joint interests in the Nelson Act and the earlier government, the General Council of All Chippewas of Minnesota, which formed in 1913 and dissolved in 1927.

On June 2, 1935 there was a notice to elect delegates for the purpose of forming a "General Chippewa Counsel." On June 27, sixty-two delegates meet in Cass Lake for the first time. Delegates expressed serious concerns that White Earth would dominate if a single government was organized. In addition, delegates expressed a strong desire for power to reside at the local level. Yet, little was done to address these concerns. Munnell utilized sample constitutions provided by the BIA and held several meetings at which a constitution was drafted and revised. The draft constitution was submitted to the Indian Office on November 6. On May 23, the Secretary of Interior signed an order calling for a referendum on the proposed constitution and by-laws. The original MCT Constitution was adopted in a referendum held June 20, 1936 and approved by the Secretary of the Interior on July 24, 1936, pursuant to the authority granted in the 1934 Indian Reorganization Act.

Election Results: Adopt or Reject the proposed Constitution of the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe:

A Corporate Charter accompanied the MCT Constitution, ratified on November 13, 1937, it was ultimately revoked by an act of Congress on February 12, 1996 (Sec. 13). This original Constitution had a system of delegates and the Tribal Executive Committee (TEC). Up to two delegates were elected annually from each community within each reservation.

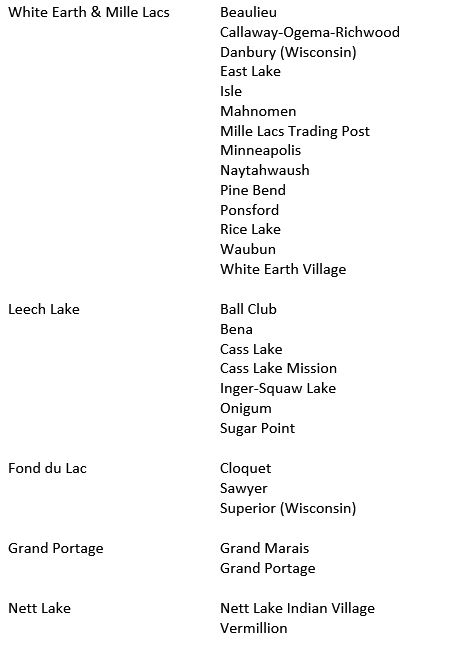

Designated districts and communities initially approved:

The number designated districts and communities changed over time, so the number of delegates varied but there were about 65 elected delegates. The delegates were elected on the first Monday in May and were required to meet in Cass Lake within 15 days to select two people from each reservation to serve as the Tribal Executive Committee (TEC). They also selected who was going to be the President, Vice President, Secretary and Treasurer. Ordinances and resolutions had to be approved by both the delegates and the TEC. Munnell served on both the TEC and in the TEC position of Treasurer. The BIA heavily influenced the government in those early years.

Article XI of the original MCT Constitution stated, "each reservation and district or community may govern itself in local matters in accordance with its customs and may obtain, if it so desires, from the TEC a charter setting forth its organization and powers." Reservations did organize local governments via the charters, which were also influenced by the BIA. For example, White Earth created the White Earth Reservation Council, which had 9 members.

Membership (citizenship) within the MCT was debated for a long time, our leaders at that time wanted all descendents included in membership and passed several resolutions that were rejected by the Secretary of the Interior. Finally, after decades of pressure, they agreed to using the 1/4 degree MCT blood quantum as the requirement for enrollment that we still have in effect today. See pieces of history on these conversations here.

Our Constitution has changed significantly overtime with referendums approved by voters and the Secretary of the Interior. The first changes happened by a referendum of voters in 1963, the Assistant Secretary of the Interior approved the “Revised Constitution” on March 3, 1964. These major changes included removing the local charters, eliminating the Tribal Delegates and creating the Reservation Business Committee structure, implementing a 1/4 degree MCT blood quantum as a requirement for enrollment, and changing term limits for elected officials from 1 year to 4 years.

Two more changes were approved by voters and the Secretary of the Interior in 1972. Footnotes on the MCT Constitution, 1972 version, highlight changes: 1) Voting age was changed to 18 and 2) Candidates for office must be at least 21 years of age as well as enrolled in and reside on the reservation of their enrollment. Before the 1972 constitutional amendment, the MCT acted more like one. People were eligible for services on any of the six reservations and could even run for office on any reservation as long as they were enrolled in the MCT. Over time, these changes have lead to separation issues between the six reservations, which continue to impact us today.

Two more changes to the MCT Constitution were approved by voters, and the Secretary of the Interior in 2005/2006. Almost 83% of the members who voted on November 22, 2005 approved two measures: 1) Proposed Amendment A: Candidates for tribal office need to be residents of their respective reservation at least a year prior to an election and must be at least 21 years of age (4,127 to 846) and 2) Proposed Amendment B: anyone convicted of a felony or a lesser crime involving theft, misappropriation, or embezzlement of money, funds, assets, or property of a Tribe.

The current MCT Constitution can be changed by a vote of the people, 20% of the resident voters or 8 members of the TEC can ask the Secretary of the Interior to call for a referendum where all MCT members are then allowed to vote on a proposed change. The Constitution requires that 30% of those entitled to vote must do so for a valid election. If 30% percent vote and if a majority of the voters agree, then the Secretary of the Interior approves or rejects the change.

Unfortunately, our current version of the MCT Constitution creates confusion and disagreement because the interpretations of the various sections combined with the TEC Interpretations and Ordinances sometimes differ.

The Anishinaabe/Ojibwe/Chippewa have a complex history. There are many different versions and perspectives on this history and there is always more history to be told and written. Below is some brief historical information as well as a list of additional resources.

Creation Story

There are many different versions of our creation story. Many people have been taught: “When Ah-ki’ (the Earth) was young, it was said that the Earth had a family. Like in a family, they had responsibilities both spiritually and physically. The Creator of this family is Kitchie Man-i-to’ (Great Mystery or Creator). He is like the great grandfather who has all the knowledge, wisdom and is always there…in a spiritual sense. Nee-ba-gee’-sis (the Moon) means heavenly being that watches over us while we are sleeping in the spiritual sense, and is referred to as Grandmother because she, like in all families, watches over us while we are sleeping in a physical sense. Gee’-sis (the Sun) means heavenly being watching us during the day. And is also referred to as Grandfather because he is the one who has the responsibility of watching over us during day. The Earth is said to be a woman and is also referred to as our mother because she gives you life, protects, and nurtures you. In this way it is understood that a woman preceded man on Earth.

Long ago, Kitchi Manitou had a dream: He saw the sky filled with the sun, earth, moon and stars. He saw the earth covered with mountains and valleys, lakes and islands, prairies and forests. He saw trees, flowers, grass and fruit. He saw all manner of beings walking, flying, crawling and swimming. He saw birth, growth, and death. And he saw some things that lived forever. Kitchi Manito heard songs and stories, he touched wind and rain, he experienced every emotion and he saw the beauty in each of these things.

After his dream, Kitchi Manitou made rock, water, fire and wind. Into each he breathed life and to each he gave a different essence and nature. From these four elements Kitchi Manitou created the stars, sun, moon and earth. Kitchi Manitou gave special powers to enhance all of his creations. To the sun he gave the power of light and heat. To the earth he gave growth and healing. To the water he gave the power to purify and renew. And to the wind he gave the power of direction, voice of music and the breath of life.

On the new earth, Kitchi Manitou made mountains, valleys, plains, lakes, islands and rivers. Everything had its place on the new earth. Next, Kitchi Manitou sent his singers in the form of birds to the Earth to carry the seeds of life to all of the sacred directions. Four Directions: Wauban (east), Shawan (south), Ningabian (west) and Keewatin (north). Two other sacred directions were the Sky above and the Earth Below. In this way life was spread across the earth. The Creator made the plants. There were four kinds: flowers, grass, trees, and vegetables. To each plant he gave the spirit of life, growth, healing and beauty. And he placed each one where it would be most beneficial. Kitchi Manitou then created the animals and gave each of them special powers. All of these parts of life lived in harmony with each other.

Kitchi Manitou then took four parts of Mother Earth and blew into them using a Sacred Shell. From this union of the Four Sacred Elements and his breath, man was created.

It is said that Kitchi Manitou then lowered man to the Earth. Thus, man was the last form of life to be placed on the Earth.” (from http://tmbci.org/history/)

Link to Phillip Brodeen presentation on MCT Constitution history, presented at the MCT Constitution Meeting in Mille Lacs on August 22, 2017

Federal Indian Policy

Excerpts from "Indian Tribes as Sovereign Governments" A Sourcebook on Federal-Tribal History, Law, and Policy by the American Indian Resources Institute.

1532 – 1789 Pre-Constitutional Policy

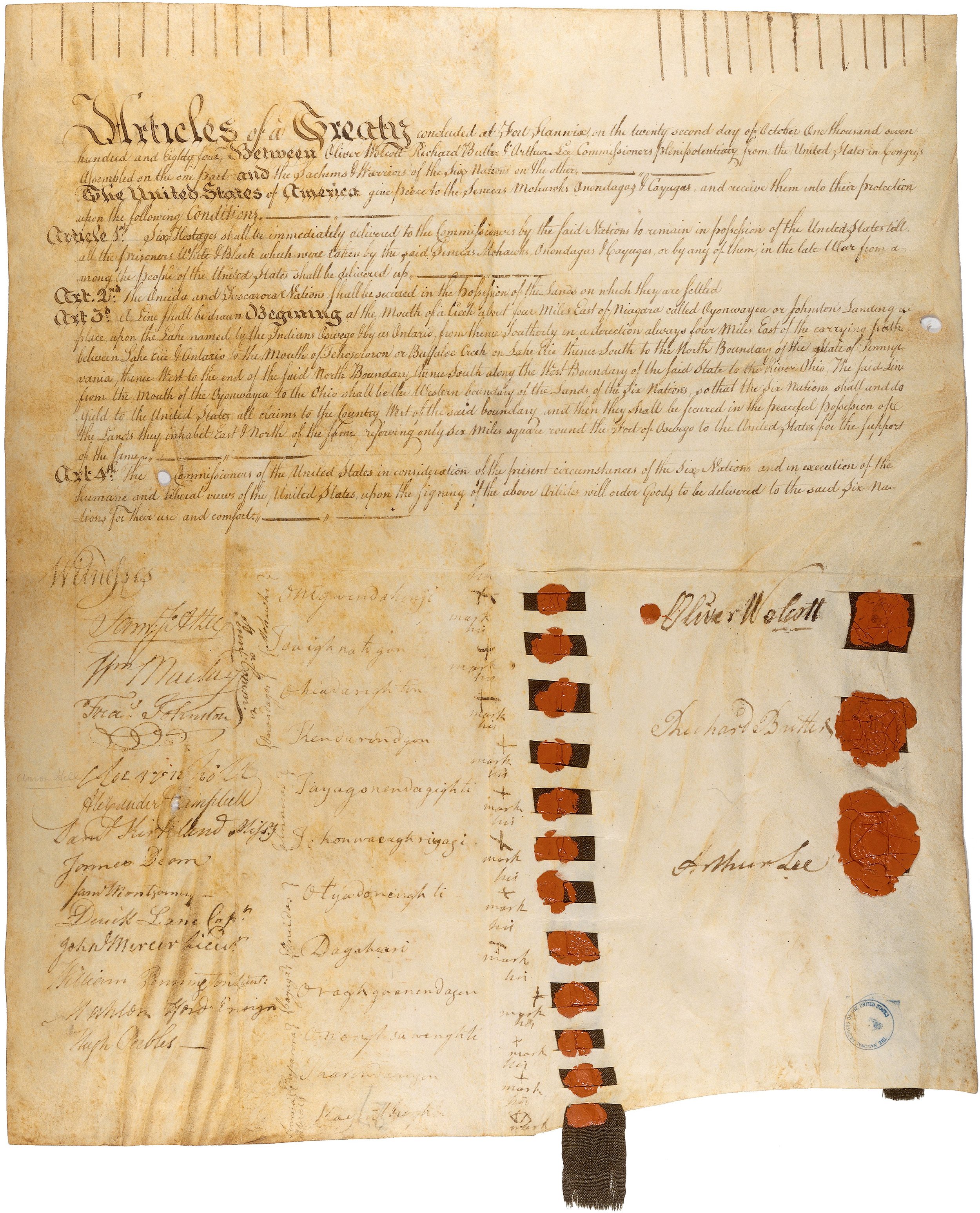

The Articles of Confederation (1781), were ambiguous concerning state and federal power over Indian matters. They gave the federal government “sole and exclusive” authority over Indian affairs, “provided that the legislative right of any State within its own limits be not infringed or violated.”

1789 – 1871 The Formative Years

The new Constitution lodged broad power in Congress under the Indian Commerce Clause, giving Congress the right to regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian Tribes.

Congress established a program regulating Indian affairs. The Indian Trade and Intercourse Act of 1790 represented congressional policy to implement the treaties and established the basic features of federal Indian policy. The Act made virtually all interaction between Indians and non-Indians come under federal control and prohibited the sale of Indian land without federal consent.

Until 1871, Congress dealt with individual tribes by formal treaties. Early cases clarifying these treaties established the basic elements of federal Indian law:

The trust relationship: Indian tribes are not foreign nations, but constitute “distinct political” communities

Tribal governmental status: Indian tribes are sovereigns, that is, governments, and state law doesn’t apply within reservation boundaries without congressional consent

Reserved rights doctrine: Tribal rights, including rights to land and to self-government, are not granted to the tribe by the United States. Rather, tribes retained such rights as part of their status as prior and continuing sovereigns

Beginning in the 1830s, many tribes across the country were removed from their aboriginal lands to other lands.

In 1871 Congress provided that the US would no longer make treaties with Indian tribes; all rights under existing treaties, however, were protected.

The reservation system began during the treaty-making era and continued to expand as reservations were added by statute and executive order. The reservation system is the principal means by which “Indian Country” was established. Indian Country is the starting point for analysis of jurisdictional issues.

1871 – 1928 The Era of Allotment and Assimilation

Originally, reservation land generally was owned communally by the tribe. Then, in 1887 Congress passed the General Allotment Act (also known as the Dawes Act). The Act delegated authority to the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) to allot parcels of tribal land to individual Indians. Large amounts of tribal land not allotted were opened for home-steading by non-Indians. Indian landholdings decreased from 138 million acres in 1887 to just 48 million acres in 1934. The effect was the “checkerboard” pattern of ownership by tribes, individual Indians, and non-Indians.

The allotment of lands was one of several policies followed during the era that were intended to assimilate Indians into larger society. BIA boarding schools were established, where Indians were required to abandon their languages, native dress, religious practices, and other traditional customs. The suppression of the Ghost Dance resulted in the Wounded Knee Massacre of 1890. Under the Major Crimes Act of 1885, the federal government took jurisdiction from the tribes for dealing with certain criminal acts – an erosion of tribal sovereignty.

Many Indians had become US citizens upon receiving allotments or by special provisions in treaties or statutes. As a means to both provide equity and promote assimilation, all Indians were made US citizens in 1924.

1928 – 1945 Indian Reorganization

The Meriam Report of 1928 set the tone for a reform movement in Indian affairs. This study publicized the deplorable living conditions on reservations and recommended that health and education funding be increased; the allotment policy be ended; and tribal self-government be encouraged.

The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 (IRA) sought to promote tribal self-government by encouraging tribes to adopt constitutions and to form federally chartered corporations. Tribes were given two years in which to accept or reject the IRA. 184 tribes accepted it, motivated perhaps by the Act’s objective of eliminating the Department of the Interior’s absolute discretionary power over them. Many tribes, however, viewed the IRA’s prescribed method for establishing tribal governments as perpetuating the paternalistic assimilation policy. 77 tribes therefore rejected the IRA.

The most significant contribution of the IRA was to promote the exercise of self-governing powers, tribes were influenced by it to formalize their political authorities in new ways. On some reservations, traditional leaders were excluded from this process deliberately or unintentionally.

1945 – 1961 The Termination Era

In 1946 Congress created a method for Indian tribes to obtain damages for the loss of tribal lands, known as the Indian Claims Commission, the special court was authorized to hear and decide causes of action from action prior to its creation. Tribes were given five years (until 1951) to file their claims.

House Concurrent Resolution 108 was adopted in 1953, called for ending relationships as rapidly as possible. Some tribes were terminated from their federal relationship and lost their federal status (some have now been restored). This has become known as the termination experiment.

Many tribes saw their sovereignty diminished during the termination era, even if they were not actually terminated. The most important piece of legislation passed is Public Law 280, passed in 1953, which was the first general federal legislation extending state jurisdiction to Indian Country.

Other assimilation tactics implemented during the late 1940s and early 1950s included the transfer of many educational responsibilities to the states and the “relocation” program to encourage Indians to leave the reservations and seek employment in various metropolitan centers.

1961 – Present The “Self-Determination” Era

The abuses of the termination era led to the reforms of the 60s, 70s, and 80s. This period has been characterized by expanded recognition and application of the powers of tribal self-government, and by the general exclusion of reservations from state authority; progress has not been uniform.

The Indian Civil Rights Act of 1968 (ICRA) extended most of the protections of the Bill of Rights to tribal members in dealings with their tribal governments and allowed Public Law 280 states to “retrocede” or transfer back jurisdiction to the tribes and the federal government.

The Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975 (often referred to as “638”) encouraged tribes to assume administrative responsibility for federally funded programs that were designed for their benefit and that previously were administered by the BIA and US Indian Health Service.

The 1978 the Indian Child Welfare Act required many adoptions and guardianship cases take place in tribal court and established strict set of preferences for child custody proceedings that begin in state court, including notification to the child’s tribe. The American Indian Religious Freedom Act pass in the same year, recognized the importance of traditional Indian religious practices and directed all federal agencies to insure that their policies will not interfere with the free exercise of Indian religions.

The years since 1871 demonstrated the folly of legislatively determining how Indians should live. Their histories show a remarkable talent for determining such matters for themselves. Return the right of decision to the tribes – restore their power and hold the dominant society at arm’s length, and to bargain again in peace and friendship. Only by possessing such power can the tribes make useful choices within the social environment encompassing them.

- D’Arcy McNickle, 1949

Tribes and the Federal Trust Relationship

The trust relationship between the United States and American Indian tribes has many unique features. Although the relationship may have begun as a force to control tribes, even to conquer them, it now provides federal protection for Indian resources and federal aid of various kinds in development of these resources.

The concept of the federal Indian trust responsibility was evident in early federal laws; it was first announced in Chief Justice Marshall’s decision in Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831) where the tribe filed suit to keep the state of Georgia from enforcing state laws on tribal treaty lands. The Court stated the tribe was neither a state nor a foreign nation under the US Constitution and therefore was not entitled to bring the suit initially in the Supreme Court. A year later in the Supreme Court decision in Worcester v. Georgia the status of Indian tribes as self-government entities was reaffirmed.

Under the special government-to-government relationship, Indian tribes receive some benefits not available to other citizens like Indian preference policies, special health and education benefits and hunting and fishing rights. These rights, duties, and obligations which make up the trust relationship exercised through the Secretary of the Interior exist only between the United States and those Indian tribes “recognized” by the United States.

An Indian group is a federally recognized tribe if: (1) Congress or the executive created a reservation for the group either by treated, statutory agreement, executive order, or other valid administrative action; and (2) the US has some continuing political relationship with the group such as providing services through the BIA. Indian groups situated on federally maintained reservations are considered tribes under virtually every statute that refers to Indian tribes.

The Interior Department reviews or approves certain tribal legislative actions, some of which concern Indian property and resource dealings. In recent years there has been a great deal of controversy concerning the Secretary’s administering on mineral leases on reservations and approval of water use ordinances, land use ordinances, and mineral tax ordinances. Another area of dispute involves general secretarial review of tribal ordinances – an issue that arises for many tribes with IRA constitutions that include a clause requiring such secretarial review.

The most current version of the IRA can be found here.

Treaties

Treaties are nation-to-nation agreements among sovereign entities – political groups with the ability to set rules for their own communities, determine their own membership, care for their own territory, and enter agreements with other sovereign entities. The sovereignty of Ojibwe people – recognized with that of other American Indian groups in the US Constitution – is not a product of the US political system. It existed before the US existed, it was retained in part through treaties, it exists today. Learn more at: Why Treaties Matter.

Click on the links below to learn more about each treaty:

1837 Land Cession Treaties with the Ojibwe & Dakota Chippewa signed July 29, 1837 at present-day Mendota, MN, Sioux signed September 29, 1837 in Washington, D. C.

1847 Ojibwe Land Cession Treaties Chippewa of the Mississippi & Lake Superior Signed August 2, 1847 in Fond du Lac (Duluth), Minnesota, Pillager Band of Chippewa Indians Signed August 21, 1847 at Leech Lake, Minnesota

1854 Ojibwe Land Cession Treaty Signed Septmeber 30, 1854 at Lapointe, WI

1855 Land Cession Treaty with the Ojibwe Signed February 22, 1855 in Washington, D. C.

1863 & 1864: Land Cession Treaties with the Ojibwe (Mississippi, Pillager, Lake Winnibigoshish Bands) Chippewa of the Mississippi, Pillager and the Lake Winnibigoshish Bands signed March 11, 1863 and May 7, 1864 in Washington, D. C.

1863 & 1864: Treaties with the Chippewa Red Lake & Pembina Bands Signed October 2, 1863 at “Old Crossing,” MN and April 12, 1864 in Washington, D. C.

1866 Treaty with the Chippewa – Bois Forte Band Signed April 7, 1866 in Washington, D. C.

1867 Treaty with the Chippewa of the Mississippi Signed March 19, 1867 in Washington, D. C.

Click here for the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe website